Jul

3

Andrew Young FSI

July 3, 2012 | 3 Comments

BBC World Service radio leaves Bush House this year. The final broadcast will be a news bulletin on 12th July at midday UK time (Newshour’s final broadcast was on the night of Sunday 1st July, podcast here) so I’ve decided to commemorate the move by trying to find out who Andrew Young was.

This fine plaque sits on the southern side of Bush House’s central block facing the northern side of St. Mary le Strand. It’s next to the portico where all the BBC smokers decamped to once the ban kicked in. I’ve passed it regularly since late 2005 and have always wondered just who it was giving me a rather baleful Victorian stare with just a hint of disapproval.

Now when it comes to public memorials in London it’s rare for there to be so little information around on the web . . . somebody, somewhere musta written something right? Wrong. In this case not a peep. So allow me . . . the information below was kindly provided by the archives dept of English Heritage. Thanks also to the British Library for invaluable details gleaned from a small booklet of 25 pages or so by Margaret Bryant entitled Andrew Young: A brief account of his life and work as a public officer of London. This slim but well-presented tome was produced as part of his memorial and contains a preface by A.G. Gardiner.

The man

First off those strange initials: F.S.I, they stand for Fellow of the Surveyors Institute (a body over which he became president in 1920) which gives us a clue as to Mr Young’s profession. He became the London Councty Council’s (LCC) first head of the Surveying and Valuing dept, entering service at the end of 1889 and staying for 25 years. This is the timespan specified on the plaque; his life lasted a lot longer.

He was born in London 28th June 1848 but his family hailed from Duns, Berwickshire. He was baptised at Oxendon Chapel, Haymarket which no longer exists. Educated at a private school in Brixton.

In May 1873 he married Henrietta Spurier of Bristol. They had 10 children and 1 died in infancy. A son, James,

died in WWI on the attack in Zeebrugge on St George’s day 1918.

He died 3rd February 1922 of septic pneumonia in the South of France where he’d taken his wife to recuperate from an illness. His remains are still buried in France.

The memorial

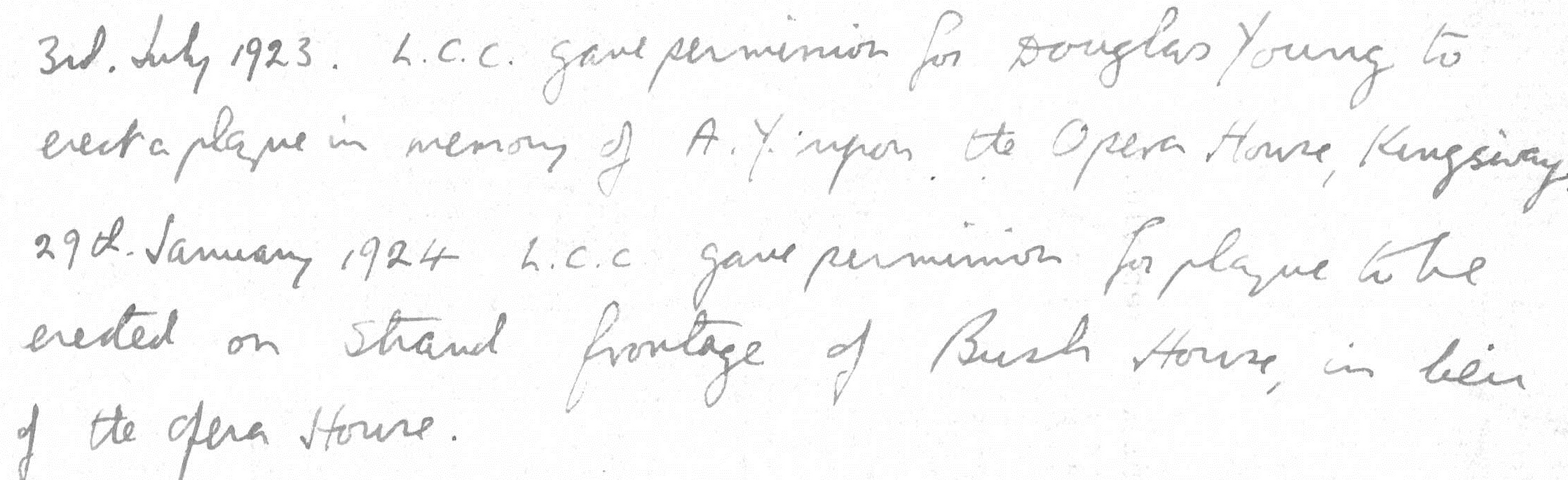

It is bronze and was designed by Eric Bradbury and unveiled by Herbert Hunter JP, chairman of the LCC for 1924 -1925. Prior to the unveiling on 28th May 1924, the LCC gave permission for Douglas Young (I assume a son) to erect a plaque on Opera House on Kingsway, however this was changed a few months later in January 1924 when the LCC decided the plaque should go on Bush House.

Did the LCC know that the Opera House theatre days were numbered (it was demolished in 1956 and is now an office block housing the Peacock Theatre) . . . or did they think Bush House simply a better location? It’s unclear but both locations reflect Mr Young’s close association with the entire Holborn to Strand stretch.

The Work

Now the LCC was the successor to the London Metropolitain Board of Works whose own demise came about owing to scandals. Andrew had made a name for himself as head surveyor of the London School Board (he campaigned for large playgrounds the benefits of which are still there in many schools today). When they were looking for someone to do the same job for the newly-formed LCC there was only one choice; as Margaret Bryant says he had a “certain loyalty to the public interest which had the character of a religion”. She then adds a line which has particular resonance in today’s world of home-flipping MPs, moats & duck houses:

“Nothing is more rare than the suspicion of dishonesty in the public official class. But the probity of Andrew Young was a legend”.

How times have changed, anyone uttering this today would be laughed out of town.

Andrew spent time in “filthy and verminous tenements” and believed strongly that the solution to slums of London was total redevelopment. As Mrs Bryant writes: “He was officially responsible for all questions of compensation in connection with street improvements, housing schemes, slum clearances, open spaces, the erection of asylums and fire stations; for the arrangemnts made for main drainage, tunnels beneath the river, the approaches to bridges, and for the site of the new County Hall”

His work as a valuer meant whenever the council wanted to buy land or compulsorily purchase property for some kind of project he was the one who had to deal with landowners. Invariably the landlords would try to under or over-value their properties in order to maximise profits or minimise taxes . . . such is life and I suspect anyone working in a local authority today will be nodding knowingly as they read this. Some of you may even have been offered a backhander or two . . . good luck trying that with Andrew Young, his puritanical upbringing (Mr Gardiner compares him to John Knox himself!) was enough to put off anyone trying to pull a fast one:

“His work had he been a man of another mettle, would have laid him open to attacks and influences that would have been hard to resist. He not only resisted them but enjoyed fighting them . . . he fought the claimants to extravagant compensation with an intensity of conviction and a thoroughness of knowledge that saved London many hundreds of thousands of money”

Andrew was a prime instigator of the principle of “betterment” which is essentially a rather mean-spirited piece of legislation which still exists today in the UK. As the current UK Valuations Office Agency states: The term “betterment” in terms of compulsory purchase refers to any increase in the value of a claimant’s retained land resulting from the implementation of a scheme of public works. The recoupment of betterment from landowners has a long history dating back to the rebuilding of London following the Great Fire of London in 1666 and beyond.

In those days there was no council tax so it’s understandable but today it’s hard to fathom quite why any government should be entitled to recoup a gain to a citizen that’s come about because the council has spent that citizen’s own money in his neighbourhood. But I digress, back in Andrew’s day the LCC really needed the cash. The Metropolitain Board used to carry out works using a grant from the government (based on coal and wine duties I believe) but this was abolished leaving the LCC “no fund with which to defray costs.” Bryant explains: “The whole burden (of paying for public works) must fall on the occupying ratepayer, unless some method could be found of making the ground landlords bear part of the cost. The progressive council . . . fell back on an attempt to secure for the London public the increase in value due to improvements which would otherwise go to increase the wealth of the ground landlords”

In today’s world we have the controversial council tax — payable by all households and rising incrementally based on the value of your house which, if it rises, results in a higher council tax charge . . . so in a way a mild form of betterment levy still exists.

Andrew really needed funds because he had grand plans. Plans which would become associated with him forever. In 1899 the LCC decided to totally revamp the area between Holborn and the Strand. We now know this area as Kingsway and Aldwych (Ald Wych = Old Market, the name chosen to remind Londoners of what once stood on this site in medieval times) but in Andrew’s time it was in his view a festering slum. However, Peter Berthoud’s excellent blog here tells a different story. Sure, the streets weren’t full of the kind of architecture that would bother Edinburgh’s New Town but it doesn’t look to me like a particularly “filthy and verminous” part of town. I suspect that like many council workers today Andrew was petrified of appearing to have nothing to do: if you weren’t redeveloping, changing or altering in some way then you weren’t doing your job. However, what came after was a vast improvement: Kingsway and Aldwych today are both very wide thoroughfares (100 ft exactly) — much more spacious than other streets in the vicinity and it’s all down to his planning. Indeed if it weren’t for the horrendous choking traffic this part of town it would be just the kind of avenue you could stroll down on a summer’s day admiring the view.

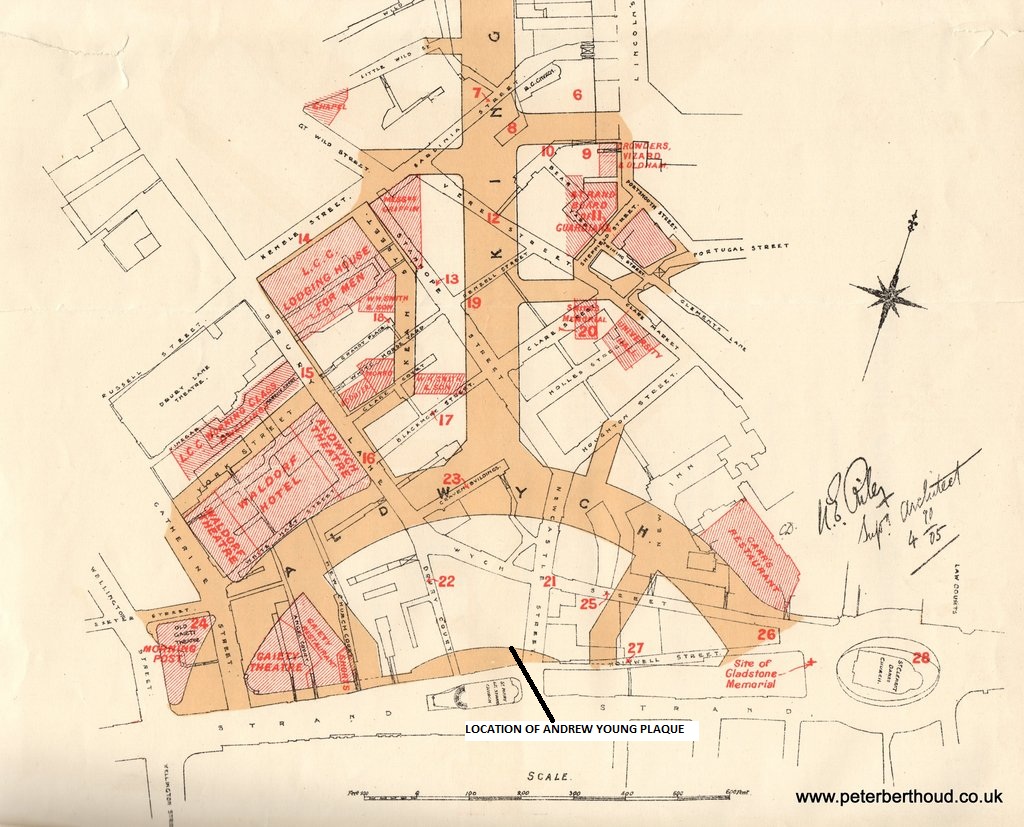

The Kingsway/Aldwych development overlaid onto the streets they replaced. Bush House sits in the centre of Aldwych.

The map on Peter’s site showing the old streets overlaid with the new proposals’ outline gives you an idea of the scope of the redevelopment. What is not shown on this map is the underground tramway which extended all the way up to Southampton Row. Today it’s a car tunnel which they close regularly when lorries and other high-sided vehicles get stuck.

The best epitaph I can leave you with regarding Andrew is written on his plaque but if that’s not enough for you then here’s Margaret Bryant; once again, can you imagine this being said about someone in such high public office today?

“He dealt with matters involving millions in money . . . and at the end he died a poor man, rich only in the affection of those who knew him”.

UPDATE 7/7/12: Andrew Whitehead has a nice account of one of Aldwych’s most notorious spots: Holywell Street. It was quite a den of iniquity which possibly gives a clue as to Andrew’s motives for wanting to raze the place.

Comments

3 Comments so far

Great to find this article about my great grandfather. My brother has a plaster reproduction of the plaque. Thank you for this Mr Coletti, very interesting!

Have been searching to find information on Andrew Young and the plaque for a while and, like you, couldn’t find anything anywhere,… so, was delighted to come across your extremely informative article on him. Thank you!

[…] Behan directed us to Coletti where we discovered that the plaque was “designed by Eric Bradbury and unveiled by […]